You can’t tell how many apples are in a seed.

In May of 2010, I, Art Rhyno, Nicole Noel and late and sorely missed Jean Foster hosted an unconference at the central branch of the Windsor Public Library.

Unconferences are seemingly no longer in vogue, so just in case you don’t know, an unconference is a conference where the topics of discussion are determined by those in the room who gather and disperse in conversation as their interests dictate.

The unconference was called WEChangeCamp and it was one several ChangeCamp unconferences that occurred across the country at that time.

At this particular unconference, 40 people from the community came together to answer this question: “How can we re-imagine Windsor-Essex as a stronger and more vibrant community?”

And on that day the topic of a Windsor Hackerspace was suggested by a young man who I later learned was working on his doctorate in electrical engineering. What I remember of that conversation four years ago was Aaron explaining the problem at hand: he and his friends needed regular infusions of money to rent a place to build a hackerspace so they needed a group of people who would pay monthly membership fees. But they couldn’t get paying members until they could attract them with a space.

Shortly thereafter, Aaron - like so many other young people in Windsor- left the city for work elsewhere. It’s a bit of an epidemic here. We have the second highest unemployment rate in Canada and it’s been said that youth unemployment rate in Windsor is at a staggering 20%.

In Aaron’s case, he moved to Palo Alto, California to do robotics work in an automotive R&D lab.

In the meantime back in Windsor, in May 2012, I helped host code4lib North at the University of Windsor. We had the pleasure to host librarians from many OCUL libraries over those two days as well as staff from the Windsor Public Library. Also in the audience was Doug Sartori. Doug had helped in the development of the WPL’s CanGuru mobile library application. He came to code4lib north because he was was curious about the first generation Raspberry pi that John Fink of McMaster had brought with him. You have to remember that in 2012 that the Raspberry Pi - the $40 computer card - was still never very new in the world.

A year later, in May 2013, Windsor got its first Hackerspace when Hackforge was officially opened. The Windsor Public Library graciously lent Hackforge the empty space in the front of their Central Branch that was previously a Woodcarver’s Museum.

When Hackforge launches, Doug Sartori is president and I’m on the board of directors.

In our 20 months of our existence, I’m proud to say that Hackforge has accomplished quite a lot for itself and for our community.

We’ve co-hosted three hackathons along with the local technology accelerator WETech Alliance.

The first hackathon was called HackWE - and it lasted a weekend, was hosted at the University of Windsor and was based on the City of Windsor’s Open Data Catalogue.

HackWE 2.0 was a 24-hour hackathon based on residential energy data collected by Smart Meters and was part of a larger Ontario Apps for Energy Challenge.

And the third HackWE 3.0 - which happened just this past October - had events stretched over a week and based on open scientific data in celebration of Science and Technology week.

We’ve hosted our own independent hackathons as well. Last year Hackforge held a two week Summer Games event for people who wanted to try their hand at video game design. Everyone who completed a game won a trophy. My own video game won the prize for being the Most endearing.

But in general, our members are more engaged in the regular activities of Hackforge.

They include our bi-weekly Tech Talks that our members give to each other and the wider public, on such topics as Amazon Web Services, slide rules, writing Interactive fiction with JavaScript, and using technology in BioArt.

We have monthly Maptime events in the space. Maptime is an open learning environment for all levels related to digital map making but there is a definite an emphasis on support for the beginner.

This photo is from our first Windsor Maptime event which was dedicated to OpenStreetMap. There are Maptime chapters all around the world, and the next Maptime Toronto meeting is December 11th, if you are curious and if you near or in the GTA.

The Hackforge Software Guild meets weekly to work on personal projects as well as practicing pair programming on coding challenges called katas. For example, one of the first kata challenges was to write a program that would correctly write out the lyrics of 99 bottles of beer on the wall and one of more recent is how to code bowling scores.

We also have an Open Data Interest group and we are going to launch our own Open Data portal for Windsor’s non-profit community in 2015. We’re able to do this because this year we have received Trillium funding to hire a part-time coordinator and to small pay stipends to people to help with this work.

Our first dataset is likely going to be a community asset map that was compiled by the Ford City Renewal group. Ford City is one of several neighbourhoods in Windsor in which more than 30% of the population is have income levels that at poverty level. Average incomes of those from the the City of Windsor as a whole isn’t actually that much less than average for all of Canada - its just that we’re just the most economically polarized urban area in the country. That’s one of the reasons why, in January Hackforge is going to be working with Ford City Renewal to host a build your computer event for young people in the neighborhood.

As well, our 3 year Trillium grant also funds another part-time coordinator who matches individuals seeking technology experience with non-profits such as the Windsor Homeless Coalition who need technology work and support.

Hackforge has also collaborated with the Windsor Public Library to put on co-hosted events such as the Robot Sumo contest.

And we’ve worked with the City of Windsor to produce persistence of vision bicycle wheels for the their WAVES light and sound art festival. I know it’s difficult to see but in the photo on the screen is a bicycle wheel with a narrow set of lights that are strapped to three spokes on the wheel. When the wheel spins, the lights animate and give the impression that there’s an image in the wheel - it only works with the human eye - because of our persistence of vision - and it’s something that really come across in a photo very well.

[here's a video!]

Also, the City of Windsor commissioned us to build a Librarybox for their event which I thought was really cool!

And like most other Hackerspaces, we have 3D printers. We have robotic kits. We have soldering irons, and we have lots and lots of spare electronic and computer parts. But unlike most other hackerspaces who charge their members $30 to $50 a month to join and make use their space, our hackerspace is currently free to members who pay for their membership with volunteer work.

This brings us to today in the last days of 2014.

2014 is also the year that Aaron came back to us from California. He’s now my fellow board member at Hackforge. And, incidentally, so is Art Rhyno, who - if you don’t know - is a fellow librarian from the University of Windsor.

I was asked by Scholars Portal if I could share some of my experiences with Hackforge in light of today’s theme of building community. And that is what my talk will be about today: how to use a hackerspace to build community. And I will do so by expanding on five themes.

But as you know know - we are only 2 years old, and so - this talk is really about just the beginning steps we’ve been taking and those steps that we are still trying to take. We admittedly have a long way to go.

Helping out with Hackforge has been a very rich and rewarding experience and I’ve learned much from it. And it’s also been hard work and sometimes it has been very time consuming.

All those decisions we made as we started our hackerspace were the first ones we’ve ever had to make for our new organization. This process was exhilarating but it also was occasionally exhausting. Which brings us to our first theme:

Institutions reduce the choices available to their members

The reason why starting up an organization is so exhausting can be found in Ronald Coase’s work. Coase is famous for introducing the concept of transaction costs to explain the nature and limits of firms and that earned him the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1991. Now I haven’t read his Nobel prize winning work, myself. I was first introduced to Coase when I read a book last year called The org: the underlying logic of the office by Ray Fisman and Tim Sullivan.

I also read Coase being referenced in a blog post by media critic Clay Shirky that was about about the differences between new media and old media. It’s Shirky’s words on the screen right now:

These frozen choices are what gives institutions their vitality — they are in fact what make them institutions. Freed of the twin dangers of navel-gazing and random walks, an institution can concentrate its efforts on some persistent, medium-sized, and tractable problem, working at a scale and longevity unavailable to its individual participants.

Further on in his post Shirky explains what he means by this through an example of what happens at a daily newspaper:

The editors meet every afternoon to discuss the front page. They have to decide whether to put the Mayor’s gaffe there or in Metro, whether to run the picture of the accused murderer or the kids running in the fountain, whether to put the Biker Grandma story above or below the fold. Here are some choices they don’t have to make at that meeting: Whether to have headlines. Whether to be a tabloid or a broadsheet. Whether to replace the entire front page with a single ad. Whether to drop the whole news-coverage thing and start selling ice cream. Every such meeting, in other words, involves a thousand choices, but not a billion, because most of the big choices have already been made.

When you are starting a new organization or any new venture, really, every small decision can sometime seem to bog you down. There is navel-gazing and random walks.

We got bogged down at the beginning of Hackforge. We actually received the keys to the space in the Windsor Public Library in October of 2012. Why the delay? We had decided that we would launch the opening of our space with a homemade keypass locking system for the doors because we thought it wouldn’t take much time at all.

And if we were considering how long it would take one talented person to build such a system by themselves, then maybe we would been right. But instead, we were very wrong. And looking back at it, now it seems obvious why this was the case:

We had a set of people who have never worked together before, who don’t necessarily even speak the same programming languages, working without an authority structure, in a scarcely born organization with no promise that we will succeed or survive, nor sure promise of reward.

Now it’s very important for me say that this so I'm absolutely clear - I am not complaining about our volunteers!!!

Hackforge would not have succeeded if it weren’t for those very first volunteers who made Hackforge happen in those early days when we were starting with nothing.

And the same holds to this day. When we say that Hackforge is made of volunteers, what we are really saying is that Hackforge = volunteers.

Our volunteers are especially remarkable because -- like all volunteers - they give up their own time that’s left over after their pre-existing commitments to work, school, family and friends. In volunteer work, every interaction is a gift. But, that being said, not every promise in a volunteer organization is one that is fulfilled. Sometimes you learn the hard way that first thing on Tuesday means 3pm.

But the delay wasn’t just from the building of the system. Once it was built, we then we had to make sure that the keypass system was okay with the library and that it was okay with the fire marshall. And we had to figure out how who was going to make the key cards, how they were going to be distributed and how we would use to decide who would get a keycard to the space and who would not. Ultimately, it took us 8 months to figure this all of this out.

I wanted to explicitly mention this observation because I’ve noticed that within our own institution of libraries that sometimes when a new group or committee is started up, there is the occasional individual who interprets the slow goings and long initial discussions of the first meetings as, at best, extreme inefficiency, and at worst, a sign of imminent failure.

When in fact, we should recognize that slow starts are normal.

Culture is to a organization as community is to a city

New organizations and new ventures happen slowly and furthermore, they should happen slowly because each decision made is one that further that defines the “how” of “what an organization is”. Are we, as an organization, formal or informal? Who takes the minutes at meetings? Do we need to give a notice of motion? Do we do our own books or do we hire an accountant? Do we provide food at our events? Do we sell swag or do we give it away? How should we fundraise? How do we deal with bad actors? Every decision further defines the work that we do.

It’s very important to take the time to take these steps slowly in order to make sure that the way you do things match up with the why you do things. As I think we can appreciate in libraryland, once institutions reduce choices of their members it is very difficult - although not impossible to open them up again for rethinking and refactoring.

One of reasons why Hackforge has been very successful in its brief existence - is that it was formed with clearly articulated reasons and clear guiding principles that continue to help us shape the form of our work. And I know this, because the vision of what Hackforge should be was told to be me when I was invited to serve of the board when Hackforge began and, I can attest to the fact, that it is the same the as the one we have now.

Now, there are many different types of hacker and makerspaces: some are dedicated to artists, others to entrepreneurs, while others are dedicated to the hobbyist. Hackforge - in less than 140 characters has been described as this: Hackforge supports capacity building in the community and supporting a culture of mentorship and inclusivity.

More specifically, we exist to help with youth retention in Windsor. We aim to be a place where individuals who work or want to work in technology can find support from each other.

I know it might sound strange to you that we believe that our local IT industry needs support, especially when we read about the excesses of Silicon Valley on a regular basis.

But in Windsor, there are not many options for those with a technology background to find work and so, despite of the impression we give to those pursuing a career in STEM, tech jobs in Windsor can be poorly paid and the working conditions can be very problematic.

Many of the provisions in the labour law - the ones that entitle employees to set working hours, to breaks between and within shifts, to overtime and even time to eat - have exemptions for those who work in IT. I’ve been told that the only way to get a raise while working in IT in this town is to find a better paying job.

The IT industry sometimes treats people as if they were machines themselves.

Hackforge was built as a response to this environment. It was build in hopes that it could help grow something better. At Hackforge we know our strength does not come from the machines that we have in our space, but our amazing members and the time and work that they give to others.

I mean, we love 3D printers because they are a honeypot that brings curious folks into our space, but the secret is we are not really about 3D printers.

And yet if you look at all of what our media coverage we receive, you would think we’re just another makerspace that loves 3D printers and robots.

This is why it is SO important to be visible with your values, which is our second theme.

Show your work

One of the challenges that we have at Hackforge is that we don’t have very many women in our ranks. Women make up half of our board of directors but our larger membership is not representative of the Windsor community and it’s likely not representative in the other aspects of identity, for that matter, either.

We know that if we wanted to change this situation, it would require sustained work on our part. And so when we had our official launch of Hackforge last year, we, as part of the event, hosted a Women in Technology Panel that featured four women who work in IT, including the very successful Girl Develop IT from Detroit, all of whom both shared their experiences and offer strategies to make the field of technology a more inclusive environment and better place for everyone.

In the audience for that panel discussion was a representative of WEST. WEST is a local non-profit group who works and stands for Women’s Enterprise Skills Training. Starting next year, with the support of another Ontario Trillium grant, Hackforge and WEST are going to be launching a project that will offer free computer skills training workshops for women as well as trying to create a community of support, and continue to advocate for women in the IT field.

So I can’t stress this enough. You have to do your work in public if you want your future collaborators to find you.

I have also another Women in Technology story to start our third theme.

So remember I told you about unconferences? Well, the Hackforge members who run the Software Guild do something similar. Sometimes instead of coding, the folks do something like this. They write down all thing the things they want to talk about, vote for the topics and then talk the most voted topics within strict time limits. But they don’t call it an unconference:

They call it LEAN COFFEE.

I love it. It’s so adorable.

Anyway, at one of these Lean Coffee sessions, our staff coordinator suggested the topic Women in Technology. And the response she received was this: We know there’s a problem because Hackforge doesn’t have enough women. But we are not sure how to fix this.

To me, I found this statement very encouraging.

Its sad, but in these these times, when people can admit that there’s a problem without any deflection or allocation of blame is actually very refreshing.

I mean, within librarianship - we have some organizations who consistently organize speaking events made up of mostly men. Whenever I raise this matter I usually told that if the speaking topic is not about gender, then it’s not about gender. In other words, they tell me that there is no problem.

But sometimes there is a problem.

Look at this photo: from this you would never guess that it was taken in a city that is over 80% African American. This photo from the first meeting of Maptime Detroit that I attended last month. One of the first things that was said during the evening’s introduction was a simple statement by the organizer. “I want to acknowledge who isn’t this in room” And what followed was a plan to hold the next Maptime meetings, not in the mid-town Tech Incubator, but within the various neighbourhoods in the city and alongside partner organizations already working with Detroiters where they live.

So before we can be more inclusive, we need to recognize when we are not.

We can start by acknowledging who isn’t in the room. It isn’t hard to do.

Quinn Norton wrote a lovely essay about this called Count. Speaking of counting, we are now at theme four.

A mailing list is not a community

What you might find surprising is that - for Hackforge being a gathering of people who generally love love love the Internet, is that we really don’t even have a strong online space for folks to hang out in, with the exception of our IRC channel. We used to have forum software, but is was so overwhelmed with spam on a daily basis it was almost immediately rendered unusable.

Also, Hackforge doesn’t even have a listserv mailing list.

And I would go as far to say that one of the reasons why Hackforge has been as successful as we have been is in part, because that we *don’t* have a mailing list.

There’s a website that’s called Running a Hackerspace that is a collection of animated gifs that metaphorically capture the essence of Running a hackerspace. I think it’s particularly telling that there are many recurrent topics that arise this Tumblr: like the complaints that folks don’t clean up after themselves.

(And this is when I confess that when I drop by Hackforge, I am also sometimes made sad).

But the most prevalent theme in the blog is mailing list rage.

You would think this would have been a solved problem by now: how do you support project work that is done asynchronously and dispersed over geography. Many open source communities are finding that the traditional tools of mailing lists, forum software, and IRC channels are not doing enough in helping their communities do good work together. More often than not, these technologies seem to be better than boosting the noise rather than the signal.

Distributed companies like Wordpress are moving from IRC to software platforms such as Slack. As I’ve mentioned before, I’m involved with a largely self-organized group called Maptime and we also make use of Slack, which is essentially user friendly IRC, chat, and messaging along with images, file sharing, archiving and social media capture.

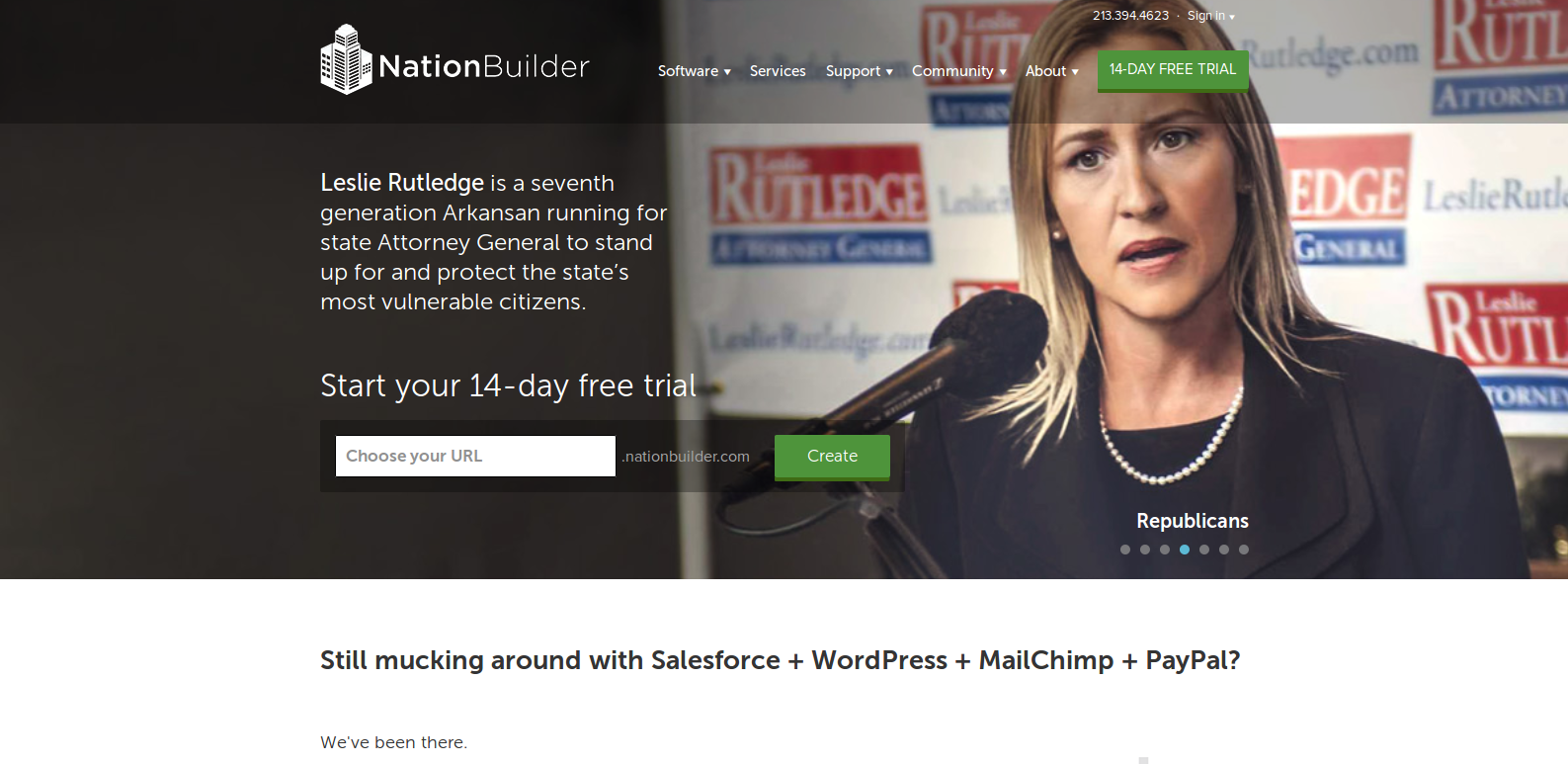

At Hackforge, we’ve recently decided to use the Jira issue tracker to manage the hacking work that we need to do in the space and we will be switching to Nation Builder software to manage our members and member communications. When activists, non-profits, and political parties are using software like Nation Builder to manage the contact info, the interests, and the fundraising of tens of thousands of people, it makes me wonder when libraries are going to start using similar software to manage the relationships it has with its community.

And at a time when my neighbours who rent the skating rink for collective use, use volunteer management software to figure out who’s turn it is to bring the hot chocolate, I would like to suggest that libraries perhaps could start using similar software to - at least - manage our internal work and communications as well. Good tools make great communication possible within organizations and our communities. They are are worth the investment.

Invest in but do not outsource community management

Before I end my presentation with this last theme, I do want to offer a caveat to everything I’ve said. If you asked all of the people who have been involved in Hackforge - those who have come by our events, spent time in the space, or even volunteered some mentoring at an event - if you asked them if they felt they were part of a community, I think most people asked would probably say, no. I think we have a wonderful group of people who have contributed to Hackforge and I think we have a group of people who have even found friends at Hackforge, but I think we still can’t call the whole of what we do "a community" - at least not yet.

Hackforge is approaching its 2nd birthday and this talk has been a wonderful excuse to reflect on what we do well and what we still need to work on.

What works for us are regular events, contests and Hackathons. We are well aware of the limitations of hackathons and how they produce imperfect work but, for us, it seems to be that that pre-defined limits and deadlines produce more work and generate more interest and excitement than unstructured free time seems to.

Unlike many hackerspaces, we don’t tend to have many group projects. The door project - as you have learned - was one of few group projects, and that one took longer than expected. In our early months, we also had a LED sign project that was never completed and actually resulted in some people leaving Hackforge in frustration.

We are a volunteer organization and as such, by the process of evolution, we are a place for the patient and the forgiving. Sometimes we have gotten our first impressions wrong.

One of the largest challenges I think we have as an organization is to be more accessible to beginners. In fact, that the feedback that we’ve been getting.

Aaron recently had a tech talk about tech talks and the message he received was that Hackforge should provide more sessions for beginners. And this is a particular challenge that we haven’t really addressed yet. We’re luckily that Hackforge has people who are both generous with their time and not afraid of public speaking and give tech talks. But many of our speakers don’t preface their talks with an introduction that a newbie could understand. They are so excited to have fellow experts in the crowd and they jump right into the code or electrical specs or what have you.

Likewise, it’s amazing and wonderful that we have regular supportive events like our member’s coding katas in which those who work with software can practice and share their coding practice with others. But at the moment, we don’t really have anything for those who want to learn how to code. And you might not be shocked to hear this, but Hackforge’s machines like our 3D printers - lack even the most basic documentation on how to use the machines.

Without expanding the work of communicating, documenting, explaining, and teaching, Hackforge won’t be able to attract new members.

Hackforge started as a top down organization. Our job as board has been to the build the systems that will allow more of the day to day work of the Hackforge to move from the board to our community and program managers. We were able to hire our managers in the middle of this year and already, they have made wonderful contributions to Hackforge. Our next challenge will be how to move more of the operational work of the managers to the members themselves.

In other words, the challenge for Hackforge is to ensure that the work that needs to be done - all of that communicating, documenting, explaining, teaching - needs to be embraced by all of its members as a community of practice. And through this practice, it’s hoped we can build a community.

So, those are my five themes for building community with a hackerspace:

Institutions reduce the choices available to their members (so choose carefully)

Show your work (so future collaborators can find you).

Acknowledge who isn’t in the room (Count is only the start).

A mailing list is not a community (Invest in tools that do better).

Invest but do not outsource community management.

The work of figuring how to get a bunch of people to come together and face a shared challenge isn’t just the way the build a community. This is also how political movements begin. It’s also how a game begins. I would like to thanks to Scholars Portal for giving me the opportunity to begin Scholars Portal Day with you all.